Georgette Heyer and the Mystery of the Dictionary

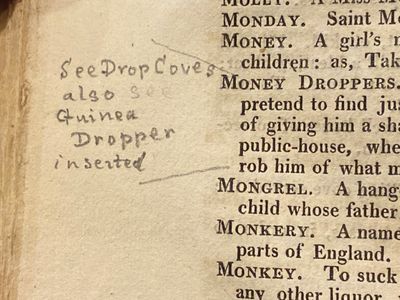

by Alice Von Kannon

(Author of Heart's Blood)

•

Could this book from a Scottish bookseller be the key to unlocking the great romance writer's incomparable world of Regency slang?

I have a mystery...

I have a mystery, and I need help to solve it.

This tale began in 2017, when I was doing research for a novel I wrote set in the Regency. I was always a hound for slang – Chris and I adored British slang from the time we met in high school. Back when we were film students, we also loved the rich vein of American slang that erupted in the 1930's and 40’s. If you’ve never seen the 1941 film Ball of Fire with Gary Cooper and Barbara Stanwyck, give it a look. An hysterically funny love letter from director Howard Hawks to this vibrant period of American cant.

In the film, the professor played by Cooper dumps the "embalmed phrases" in his encyclopedia article and leaves his academic ivory tower to “tap the major sources of slang, the streets, the slums, the theatrical and allied professions.” As my own research unfolded, Regency slang, in all its colorful eccentricity, rapidly became an obsession. I also studied the sources, as best I could two centuries later - the streets, the slums, (rookeries, they were called) as well as the theatrical and allied professions of that time. Additionally I studied the “cries of London,” the distinctive sing-song patter, mostly lost to us now, of street sellers hawking their wares.

The vulgar tongues of Francis Grose and Pierce Egan

One of the bedrocks of the study of Regency slang is the work of an artist, historian and lexicographer named Francis Grose. In 1785 he set down one of the first dictionaries of language considered vulgar at that time. He called it, in fact, Grose’s Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. It was a runaway bestseller. Now, with Grose in hand, someone who was a “flat,” an ordinary Joe, could learn the secrets of street language, the cryptic patter of carriage drivers and costermongers and street sweepers. No more wondering to what degree he’d just been insulted by a jarvy when he refused to tip him a hog.

Grose's book went through three legitimate editions before he died in 1791. He was ripped off before he was cold. Popular books like the 1795 Blackguardiana claimed to be original while robbing him freely. Over the years more legitimate editions of Grose, that actually credited the man, were published, editions with additions, each one tailored to a new audience. The 1811 “university” edition, punningly called Lexicon Balatronicum, the fool’s dictionary, supposedly added collegiate slang. There really aren’t as many changes in it, however, as in the next major reissue.

This was my favorite, the Pierce Egan updated version of 1823. Egan was essentially a sportswriter, though he was many other things, a man incredibly famous in his own time, tragically forgotten now. His comic book Life in London, published in 1821, was fabulously popular, the adventures of Tom and Jerry in the Metropolis. With its peculiar style, the thing is just riddled with slang, in a nearly musical fashion. It didn’t take long for Egan to turn his book into a play that was equally popular. He, too, was ripped off constantly, with tons of books that were unapologetically “Tom and Jerry,” or something near to it, even in France and America. Georgette Heyer’s books are drenched in the sporty lingo of Pierce Egan, which is singular, the Runyonesque chatter of boxing, horse-racing and gambling that was his specialty.

The original Francis Grose version of Vulgar Tongue is everywhere, available in reprints as well as freely distributed on various blogsites. The Pierce Egan version can be a bit harder to find. I was sick of trying to read my crappy Ulan Press smeared Xerox print-on-demand copy of it, so I decided to blow for an old edition that was properly published. But the Egan version of Grose wasn’t a perennial that got republished again and again throughout the 19th century, which limited my choices.

I found only four of the Egan editions on ABEbooks, all from 1823.

Captain Francis Grose, author, artist, antiquarian, and hero to vulgarians everywhere

The Find

One copy in Edinburgh intrigued me. It had been cut out of its original covers and rebound in Morocco leather, with thirty-two pages of additional definitions tipped in, as well as newspaper clippings and period advertisements. A possible date for the rebinding was on one of the clippings, 1925. The binding was pasteboard, almost like a notebook, making it easy to write inside.

Researchers don’t usually buy books that have been mucked up. I don’t want to try to read through someone else’s notes and highlighting. But the description from the bookstore said this thing was doubtless the property of a writer, which interested me. They thought it might have belonged to Eric Partridge, the great 20th century lexicographer and slang expert, a man whose work I knew well. They thought it might have been a research tool for a new, annotated edition of Grose he published in 1931, but when they checked, the handwriting wasn’t a match. Also, the additional material at the back had nothing to do with slang, and was just too specific on things that would probably only interest someone writing an historical novel.

The seller posted a picture, and to my surprise, I felt a little lurch of recognition. By sheer chance I’d recently read Jane Aiken Hodge’s biography, The Private World of Georgette Heyer, and I thought I recognized some of the unique handwriting, including a larger first letter with added serifs, aping illuminated manuscripts and calligraphy. I’d seen it in a very clear picture in Hodge's book, a heading on one of the drawings in Heyer’s meticulous research notes. However, I didn’t take it very seriously, assuming it was just a coincidence. But out of the four versions available, this one was overall the nicest, and very prettily bound, a thing I can never resist, so I bought it.

At this point, it's essential to insert a tiny bit of history. People nowadays are losing sight of how things were done before computers. Around 2005, elaborate memory book crafting called "scrapbooking" peaked in a vast wave of popularity, though there's been a major dieback. But much earlier, in my 20th century era, it was fairly common for people to craft personal notebooks that were really more what my mother called "pastebooks," bound volumes of individual taste, a blog site in days of yore. When I was a kid, I kept pastebooks on several subjects, like the popular TV-show Dark Shadows, while across town my future husband Chris was doing his Space Flight pastebooks about NASA, newspaper and magazine articles and collectible stickers and patches. But there was a much deeper brand pastebooking that went back as far as the 18th century, tied to research. Students, particularly in subjects like medicine, created personal journals for the massive number of class notes they had to take, and the best of them could become quite valuable, with a bright student and famed lecturer. These pastebooks, growing out of the habits of student days, were often tied to a research project.

My pastebooks were all in three-ring binders, because it was easy and cheap. If I'd had the pocket money, I might have had my favorites rebound in fine leather, like a real book. Even in the 1960s, every town of any size had a bookbinder, and it wasn't yet a lost art. All sorts of people kept pastebooks, like art students, and historians, and fans of a particular actor or writer. And collectors of research arcana, like the slang of a particular period.

The dictionary and Georgette's Heyer's world of slang

On the day the Egan book arrived from Britain, I’d nearly forgotten I ordered it. I sat down to read it and it gripped me all over again, far more powerfully than it had when I saw the bookseller’s ad, all the Heyer connections. At that point I’d read about a dozen of her Regencies, including The Spanish Bride (my first Heyer) and her Waterloo epic, An Infamous Army, and I was beginning to have a feel for her work, and for her superlative mastery of slang. This pastebook was definitely the work of a Type A neurotic, and I greatly admired it. In fact, one of the minor ironies of all this is that I can’t bear to use the thing as a reference work; just a cup of coffee sitting on my desk anywhere near it gives me a shiver. It’s too delicate, the pages too aged, to suffer regular use. The Egan version of the dictionary was the centerpiece of the volume, but the handwritten additions ran the gamut, written on pieces of blank white paper inserted into the text. The clippings and period advertisements cover things Heyer always liked to get right – the book a character buys, its price, ads for accounts of boxing mills like the one in Regency Buck, a lot of stuff about Pierce Egan, and a catalog for his publisher, Sherwood, Jones and Company, with books on everything from popular remedies to travel guides available to readers in the Regency period. Heyer was an avid collector of books, like most writers, but also of clippings, found odds and ends usable to her. She did incredibly detailed notebooks that covered all the periods she worked in.

I felt Georgette Heyer specifically in some of the added words themselves, odd words I’d only seen in her novels - for example, the word “tirewoman” is notated with its 17th century source, a word I had in my own notes, since I'd never encountered it anywhere but Heyer. The sources for the handwritten additions run the gamut, from earlier, 18th century cant dictionaries to forgotten Grub Street works like The Anti-Pamela, comic novels like The History of Pompey the Little, even 17th century songs. (The works referenced in the dictionary are listed at the close of this article.)

Another Heyer favorite is the word “gudgeon” for a fool. This word has several meanings, but originally it was a fish, one that I guess had a dumb expression on its face and was easy to catch. Beside this word in Egan, where it’s defined as "one easily imposed upon," is a handwritten reference to the obscure Queen Anne’s New World of Words from 1611. This reference work is not only incredibly long, but the bloody thing is in Italian. Subtitled A Dictionarie of the Italian and English Tongues, it was the second language dictionary to be published in England. The addition referenced it on page 439, rimbeccársela, defined as “to swallow a gudgeon, or to believe that the moon is made of green cheese.” In the research business, this is defined as “working for it.”

The purpose of some of the entries seemed to be to back up a definition in Egan/Grose by finding it used the same way in a much older work, thereby more effectively dating it, as well. Multiple meanings and spellings were also touched on; for example, the word “dab” Heyer often used, with its many and various meanings. In Venetia, a “dab” of a girl is one who’s not much on looks or charm. But often it’s seen in the term for someone who’s an adept, either a dab or a “dab hand” at something. The insert to the dictionary cites this meaning, an adept, with the word spelled “dabb,” in the 1742 novel The True Anti-Pamela, one of several take-offs on Richardson’s popular 1740 novel Pamela.

Along with blank added pages, there are pencil notes in the margins throughout the dictionary. But the notes on blank paper are in ink, while the ones on the pages themselves are in pencil. I don't think there's anything more revealing. I would never write inside a book with a pen. If I had to do it, I'd use a pencil. Anything else would be a defacement. Whoever did this dictionary subconsciously felt the same. The Egan original has already been cut out of its covers. There's no issue of preserving the value of a first edition, and so no reason not to use the pen that's used everywhere else. But no paste and no pen ever touches the original. This is someone who worked with research books, which are quite often aged and rare. I think it was someone who cringed at the thought of defacing a book. And yet, just as revealing, the pencil notes are done with the same laboriously-added serifs, to make it look more like type font.

The plot thickens

Whoever did this dictionary was a serious researcher. There's a level of labor in these added references that's staggering, all difficult and obscure. Let me cite only two examples. One is an 1811 work by James Peller Malcolm, irresistibly entitled Miscellaneous Anecdotes Illustrative of the Manners and History of Europe During the Reigns of Charles II, James II, William III and Queen Anne. In it, Malcolm references something called Mercurius Infernus, which was a newsbook or "quarto" from the 1600s. The word "tirewoman" was pulled from here, noted along with the word "gingambobs," baubles to decorate a lady, put on her by her tirewoman, a lady's maid adept at hair and jewels.

Another work referenced is the massive 1611 book by Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, What it Is, With all the Kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes and Several Cures of It. In Three Maine Partitions with their Several Sections, Members and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically Opened and Cut Up. You can see why it’s fourteen hundred pages long. Getting through it is a slog, and if you haven’t got a compelling reason, you probably won’t. The Guardian newspaper reviewed it in 2001, when the New York Times did a reprint, the first since 1932. They admitted, “The lazy browser won’t even pick this book up off the shelf, let alone open it.” Another vote here for Heyer as the author of this dictionary’s addendums, since she was anything but a lazy browser.

THE HEYER TIME FRAME

For me, these source books from the 16th and 17th century make a compelling case for Georgette Heyer as the possible owner of the dictionary. Most researchers doing the Regency wouldn’t bother with words from 1611; they’ve got their hands full with 1811. If we accept a date for the bookbinding as around 1925, we have to look at Heyer around 1925. And doing so makes it all come clear.

Georgette Heyer was a woman who moved through ten centuries of European history and stopped wherever it struck her fancy. This was particularly so in the 1920s. Her first novel was The Black Moth in 1921, set in the mid-1700s. She was only nineteen when it was published. For 1923 she did The Great Roxhythe, set in the Restoration period, around the 1660s. Her book for 1925 was set in the 1400s, Simon the Coldheart. It was followed by These Old Shades in 1926, one of her most popular books, with its slang out of the Georgian period, again, roughly in the mid-18th century; it's a reworking of characters from The Black Moth. In 1928 came The Masqueraders, also set in the 1750s after the last Jacobite rebellion. Beauvallet followed in 1929, set in the Tudor period of the mid-1500s. Next up came 1931’s The Conqueror, set in the 11th century. After that was the fun Devil’s Cub, the sequel to These Old Shades, and finally 1934’s The Convenient Marriage, with a similar time frame to Devil’s Cub. There’s an early anchor-reference to the Battle of Bunker Hill.

Breathtaking isn’t it?

For Heyer, any and all British slang is on the table. She was a brilliant young woman, already a compulsive writer. It’s incredible to think that, after her marriage in 1925, long periods were spent literally in the wild; her husband was a mining engineer before becoming a barrister. The Masqueraders was written in Tanganyika, without access to anything but the small personal library she had in tow and her memory, which must have been prodigious. Her fans know that Heyer was a bug on the 18th century, expert on the Jacobite rebellions that ran from the late 1600s into the mid 1700s. But I think, in her youth, she was simply dazzled by the epic sweep of history. All of it was her oyster, and she was going to land her personal time machine wherever she wanted.

Georgette Heyer's far-flung world of eras

“Georgian” has become a convenient shorthand for Heyer’s fans and publishers when speaking of the period her most popular books were set in. It's a word antique dealers use, but for historians it's a criminally loose adjective - it covers more than a century, from 1714 to 1830. In other words, Georgian includes the Regency, another word that can be a bit squishy. Some historians tack on the brief rein of William IV, George’s brother, and take the Georgian period all the way up to the opening of Victoria’s rein in 1837. But the Regency in question was the regency of George IV. It makes me think of the old poem by Walter Savage Landor, about the line of Hanoverian Georges parked on the throne by the anti-Catholic Whigs.

I sing the Georges four,

For Providence could stand no more.

Some say that far the worst

Of all was George the First.

But yet by some ‘tis reckoned,

That worse still was George the Second.

And what mortal ever heard,

Any good of George the Third?

When George the Fourth from earth descended,

Thank God the line of Georges ended.

Being, I suspect, a Tory at heart, Heyer probably liked that famous poem.

So, considering how many of her books in this period of the 1920s were set in the 18th century, the additional references to slang of that period make sense, beyond simply an intellectual exercise to date a particular word. However, you can’t look at the edges and ignore the centerpiece. This dictionary is built around the Egan/Grose of 1823, which points to what was coming – Regency Buck, her first Regency, published in 1935.

The verbal cavalcade of 'Regency Buck'

There’s a unique feel to Regency Buck. I even mentioned it at the time I read it in my Amazon review. Heyer seemed determined to craft a portrait of that period defined by its totality. It’s possible that, when she wrote it, it was one more stop in her time machine. Maybe she believed the Regency was a period she might not visit again. This book was going to be more than set in the Regency; it would be a picture of it in its entire. It’s wordier than her later Regencies. The detailed descriptions of Brighton Pavilion and the New Road during Judith’s curricle race are symptomatic. She manages to work in references to every Regency temple, from Almacks to White’s, every Regency sport, from cockfighting to boxing, and every major Regency rake, even if they’re only mentioned. It's also one of her rare Regencies in which an historical figure is a character, this being Beau Brummel, as if to say that he was such a symbol of the era that he had to be included. And here, for the first time, was featured the speech of the Regency, an outgrowth of Georgian but different from it, and it already flowed beautifully.

Georgette loved the music of language

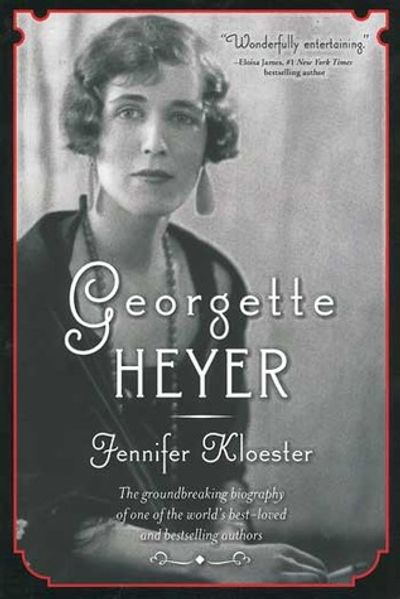

Jennifer Kloester is the ultimate source for all things Heyer, and her kind help to me is noted at the end of this article. According to Ms. Kloester, there was no version of the Francis Grose Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue listed in the catalog of Heyer’s personal research library when she died. And I quite simply find it hard to believe that she didn’t own one.

Heyer wasn’t limited to the books she owned for research. In the 1920s she joined the London Library, a private subscription library with impressive stacks and a generous attitude about lending, ten and fifteen at a time. Some writers in those days worked almost strictly in the library, as if it were an office, but Heyer doesn’t seem to have been one of these. Remember that everything you wanted to keep for reference out of a library book had to be laboriously written down, a thing I well remember myself. The various Xerox and mimeograph machines didn’t become common until the 1960’s, and you certainly didn't have one at home on your printer. Once, out of desperation, I even tried to photograph the pages of a research book. It didn’t work very well. For books that are the life-blood of a project, that are referenced constantly, a writer wants to own them, and a great personal reference library is the proud result of a lifetime of collecting. When Heyer died, she left over a thousand reference books, these apart from her extensive collection of notebooks and other materials.

I think that, if you’re going to do Regency language, a copy of Francis Grose would be an essential tool. I’m no Georgette Heyer and I’ve got four copies of it, along with an entire shelf of other related works. Both biographies of Heyer mention her treasured two-volume leather edition of Egan's Life in London, the other Regency-speak essential. In fact, they’re like bookends. I find it interesting that, in my dictionary, there’s a pencil note beside the entry for “uncle,” to “See Pierce Egan’s Life in London,” with edition and page noted. The two works are inseparable. Even within the pages of Life in London, Egan urges his faithful readers to lay hands on a slang dictionary. They just won’t get the gags otherwise.

Heyer also had her own personally compiled notebooks of slang, something I’d give a lot to see. Over the years she notated any interesting word or phrase she came across, quite often failing to note where she’d gotten it. This wasn’t for publication. Again, I’m no Georgette Heyer, but I’ve got a personal dictionary myself, on my computer. When I stumble across some incredibly colorful verbiage, from “Don’t come the cowboy with me, Sonny Jim!” to “yopping on” for talking too much, or “duds” for clothes in Dorset, a word that obviously migrated into the American West, I’m always going to write it down. This doesn’t make the Grose dictionary any the less a necessity to me, and I don’t believe it would to any other serious author writing Regency dialog.

It should be remembered that writers like Heyer, and there are few, didn’t get all their authentic period language by lifting out of a couple of dictionaries. She made herself conversant with the vast scope of Regency speech to be found in total immersion, reading the novels and journals and newspapers of the period. She was lucky in being British, for so much of the idiom and slang of her own period was a survivor of an earlier time. This is easy to see in the speech of Bertie Wooster in any P.G. Wodehouse Jeeves & Wooster or Drones Club story. Wodehouse was a contemporary of Heyer’s, and much of the sparkling chatter of Heyer's characters like Freddy Standen and Ferdy Fakenham just reeks of Wodehouse, particularly in its rhythm. But phrases like “he’s a complete hand,” a Heyer favorite, don’t appear in Grose or Egan. They were common idioms of Britain then and now, because in Britspeak, common idioms tend to have a very long shelf life.

In the end, it seems clear Georgette Heyer valued three things in her work - historical accuracy, a nice bit of humor, and felicity of language. The slang was a big part of all of these, part of the fun of writing for her. She adored the English language.

Jennifer Kloester, author of Georgette Heyer's Regency World

In Heyer's mystery novels, this deft language goes conspicuously missing. Writers played wide in the early 20th century. Along with novels, they crafted clever short stories for the vibrant market at that time, and they had to jump across genres to stay employable. I think it was a law in Britain in the 1930s that anyone who put pen to paper had to produce at least one mystery. Heyer wrote a dozen contemporary mysteries and police procedurals, called “thrillers” by the Brits, with the help of her husband, who was part of the legal system by that time. She also wrote short stories, and a few contemporary romances that she later suppressed.

Heyer herself disavowed her first thriller, Footsteps in the Dark, since she was pregnant at the time it was written, while "one husband and two ribald brothers all had their fingers in it." In the end, I think she did the thrillers for more than the money. I think she wrote them for the sake of the critics, who sometimes savaged her. This was the age of the Immortal Agatha and her many imitators. Mysteries enjoyed a reputation for books that intelligent people wrote and read. Heyer's Georgian romances, these carefully-crafted Sheridanesque comedies of manners, were dismissed as featherweight female fodder. Far worse, she was, on occasion, attacked for not getting the history right by critics who sensed how hard she was working, and liked to pounce over as little as a single word, doubting its genuineness for the period. Like all novelists, particularly comic ones, she was sometimes lambasted for supposedly crafting a world that wasn’t in the least real.

But when anyone questioned her use of a particular bit of slang, she fired back, guns blazing. This meant something to her, far beyond simple research.

Our language is an enormous part of what we are as human beings, and the words we choose a statement about our place in the world. This was particularly true in class-obsessed Britain. As Henry Higgins once sang, “An Englishman’s way of speaking absolutely classifies him. The moment he talks he makes some other Englishman despise him.” Heyer's obsession with words was more than a personal foible; it lay at the heart of the world she lived in, as well as the fictional one she built.

But in the final analysis, every author of historical fiction knows that the world he’s crafting is, in the end, a conceit. It’s essentially a fantasyland, no less than Middle Earth or the planet Arrakis. History is our anchor to that world, keeping us always connected to the core truths of human nobility and human folly. Serious authors of historical fiction live out their lives surrounded by a mountain of minutia, always struggling to “get it right,” to craft a world that at the very least might have been, one that reflects the essentials of that time and place.

For me, the great charm of Heyer’s Regency world is that, not only is it one that might have been, it’s one I long to visit. Yes, the real Regency was a world of infant mortality and typhus and grinding poverty and social injustice — all the hallmarks of human misery. Unfortunately, what’s left of American letters has become slavishly dystopian. Only the misery of humanity is granted any legitimacy or literary weight. Fiction itself is under assault from many in the elite, the novel labeled an art form that no longer has any legitimate function in the brave new world. Schools have begun to toss fiction out of the mix of what our kids read in the classroom. Poe and Hawthorne and Melville are now dead white guys. But if novels exist to perform three functions, to inspire, to inform, but above all to entertain, Heyer was a master of the craft.

One of the works cited in the dictionary, Pompey the Little, is a charming novel featuring the observations on society of a small lap dog named Pompey. In his preface, the author, the Reverend Francis Coventry, dedicates the work to Henry Fielding, the author of Tom Jones. The good reverend decries those who hold novels in contempt, pseudo-intellectuals and the generally grim-minded who take great pains to let you know they never read them. He offers a few words on the behalf of novel-writing:

"To convey instruction in a pleasant manner, and mix entertainment with it, is certainly a commendable undertaking, perhaps more like to be attended with success than graver precepts; and even where amusement is the chief thing consulted, there is some little merit in making people laugh, when it is done without giving offense to religion, or virtue, or good manners. If the laugh be not raised at the expense of innocence or decency, good humour bids us to indulge it, and we cannot well laugh too often. "

I doubt I could find an epitaph on Heyer’s work that would have pleased her more.

Detection Unlimited, one of Heyer's contemporary mystery novels

So was it Georgette's dictionary or not?

The answer is elusive

Jennifer Kloester

Jennifer Kloester is a wonderful resource for all things Heyer, author not only of one of the two bios of Heyer, but of that greatest of sourcebooks for writers and fans, Georgette Heyer’s Regency World. It’s a stunning work. The first time I read it, there were so many Post-it flags in the thing it became a bit silly. I finally pulled them all out and just reread it. Again and again and again. No, it’s not just for researchers. If you have any interest at all in the Great Georgette or in Regency London, buy it, read it, treasure it. I also recommend her website, All Things Georgette. It is indeed.

The remarkable thing about Ms. Kloester is her kindliness and her accessibility. When I decided to just break down and call her, feeling like the worst sort of nuisance, she spent an hour on the phone with me from Australia, talking to my husband Chris, as well. She’s more than a great intellect. She’s a great lady.

Ms. Kloester felt it was a possibility that the book belonged to Heyer, but was swayed in the end toward the negative by the fact that none of the handwriting she personally had samples of was a dead-match for the handwriting in the dictionary. Consequently, the choice of words and subjects wasn’t a closer for her. She sent photos of the research notes she had that Heyer had written. To my eye, there’s an undeniable similarity; both hands were very small and very tight, and more important, once again, all sketches have the formalized headings with added serifs that appear in the dictionary. (I've posted these samples below.)

She did bring up a fascinating point, that some of what’s written in my dictionary could have been put down by her husband, Ronald Rougier, who often helped Heyer in her work, particularly once that work became vital to the household finances. This hadn’t occurred to me, though I still think this was an early acquisition, when she was just getting started as a writer, in the late teens or early 1920’s. However, she did marry in 1925, the year noted on the newspaper clipping.

Ms. Kloester also put me onto a fascinating bit of trivia, suggesting it might have been the property of one Jeffrey Farnol, another British author of Regency and Georgian period romances who also wallowed in period language. Farnol was very popular in his own time, but his books are hard to get hold of now, consigned to the world of second-hand bookstores. I couldn’t even find a fan website with a brief outline of the story of each novel. Barbara Cartland, the Calamity Jane of Regency romance, actually reissued a couple of Farnol’s books in paperback form in the 1970’s, with her own name billboarded across the top as “Barbara Cartland’s Library of Love,” in letters three times as big as the author’s. But beware these editions, as they are no labour of love – she edited the original to ribbons, apparently convinced the modern reader wouldn’t have the patience to get through it.

Jeffery Farnol

I researched the deliciously odd Mr. Farnol, so tragically forgotten now. Actually, Farnol preceded Heyer by roughly two decades, and was probably an influence on her. Near the end of our conversation, Ms. Kloester herself had second thoughts, I’m certain because Farnol was so much earlier. But it’s still a possibility.

Interestingly, Farnol also had a small, tight hand when he wrote, though, based on what little is available to be seen on the Internet, there are few similarities in style of individual letters. Farnol lived in America for a time, in New Jersey, and he liked to hang out in New York, making the acquaintance of various types. Like so many writers, he had a taste for the underbelly of society, getting to know characters he would later employ in his stories. His novel The Definite Object features a millionaire safecracker in New York. Shades of A.J. Raffles! He wrote in many genres and many periods, and was probably more popular in Britain. But his first bestseller, published in 1910, was a major one, The Broad Highway, and it was a huge hit in America. It's a touching novel featuring a forced marriage tied to an inheritance, a theme Heyer used often. In fact, it's like a cross between a Heyer Regency and Hemmingway's Nick Adams road stories. I haven't figured this one out yet, but it was the bestselling book in America for 1911, and then, astonishingly, came back to be the bestseller for 1961, the age of Dr. Zhivago and Advise and Consent. This guy was not a failure. On the contrary, he wrote over forty books, dipping into many centuries, and many were bestsellers, while at least one was made into a popular film, The Amateur Gentleman, a story of boxing in the Regency. Another interesting Heyer connection.

In the prologue to The Broad Highway, the young narrator, Peter Vibart, meets a tinker on the road, and tells him about the novel he wants to write, with colorful characters like a highwayman and a boxer. The tinker advises him that, if he wants it to be popular, he should get a little blood into his book, and "if you could kill your highwayman to start with it would be a very good beginning." This is precisely the opener Heyer uses in Devil's Cub, in a very funny scene that I suspect was a valentine to Farnol.

Historians try to think like scientists, but the truth is we’re often derailed, carried off by the Romantic. Consequently, I’ve tried hard not to think this book belonged to Georgette Heyer – it just seems safer that way, and far more academically sound. Yet, I’m still in the thick of it, trying to dig deeper. Putting out this web page is part of it, in the hope someone might see something they recognize. The truth is, something in my gut still says I’ve got about a fifty-fifty shot this did, indeed, belong to her.

If anyone out there knows of another author, contemporaneous with Heyer, who also worked in Regency slang, particularly if there was a Pierce Egan or a boxing connection, I’d love to hear about it at avonkannon@aol.com

The Handwriting

I’m no handwriting expert, but when I look up things on the Internet that we know Heyer wrote, or examine examples used in her biographies, I see similarities with the dictionary. First, they were both changeable - her handwriting seemed to shift, perhaps not so much based on age as on what she was doing, and whether it was in longhand or printed. A personal letter, a series of research notes and a heading on a research drawing didn’t look the same. The other main similarity I see is that they are both a small, tight hand that only gets big and formal when labeling something.

In both my dictionary and Heyer’s handwriting there seemed to be a more or less constant shift between print, cursive and formal serif lettering, even at times within the same word. For example, many small “fs” in both of them begin as cursive script, and finish as print. Small “d” and “b” shift. At times they look more like standard cursive, with tail intact, then it shifts, and it starts probably at the top, with a closed loop for the body, and no tail of any sort. I find the small “g” in both Heyer and the dictionary fascinating, where it has been made to look like printed type. But this business of labeling images is the main similarity I see, though there are others. It seems like a mental shift, “Now I’m printing for clarity, now I’m quickly note taking, now I’m labeling,” that causes a shift in style of individual letters.

Detail from Jennifer Kloester's private collection of Heyer's writer's notebooks

But then there are others...

Images of Heyer's notes taken from Jane Aiken Hodge's The Private World of Georgette Heyer show several examples of her printed notes that are more similar to the dictionary than Kloester's later ones, especially in serif capitals for the first letter of words.

Detail of image from Jane Aiken Hodge's biography, from Heyer's ongoing medieval research. The serif capitals are a dead-match for the dictionary. The text was apparently copied down to the "g," a probable footnote in the original. I can find no other meaning.

Look at the “d” on the left-hand side of the Kloester/Heyer notebook, under a drawing of a postal stamp for franking, “To be delivered free.” It’s the same “d” that appears in the dictionary, a “d” with a little script tail, while this is not the “d” that appears in “England” and elsewhere, under John of Lancaster. This is a shift in two provable Heyer samples, and it surprised me.

I do think almost everything in the dictionary was considered by its writer to be a careful, more formal labeling type of printing, rather than hastily scribbled notes. The goal is for the additions to more closely resemble printed text. And, if its writer was Heyer, that means that what’s written on her research drawings are the samples to be looked at for a possible match.

The saga continues

So I'm asking for your help...

The one thing I don’t see, anywhere is the curving, fluid arcs of a more florid sort of handwriting, like the prettiest cheerleader had in high school. That sort of whimsy is nowhere to be seen, in provable Heyer or my dictionary. Again I’m no expert, but what I see with my own eyes is tight lettering written with a probable death grip on that pen. That is, until the headings, when the level of care and additional serifs are of interest. Personally, I think the science of graphology, attempting to gauge personality based on handwriting, is a lot of bunkum. However, it’s interesting to note that small, tight letters like this supposedly indicate an intellectual, while the florid sweep and arc is an extrovert. Heyer was a brilliant woman and anything but an extrovert.

Out of curiosity, I dug up some of my own handwriting from the long-ago past, and found it, surprisingly, more changed than I had expected. Even the tilt has changed. I always preferred printing to script, and used to indulge the little affectation of making my small “e” with two strokes, like a C with a slash across it. That sort of thing died by my thirties. By my forties, I’d forgotten entirely how to write in cursive style, and the loose, easy feel to what I’d printed was gone. Now, I seem to type everything, and I’m lucky if I can read my own grocery list. So, handwriting does drift with age for some people. Not always. Both my mother and mother-in-law retained the rigidly-enforced cursive handwriting taught to them in Catholic school to the end of their days. They were both born in 1929. I never could tell their writing apart.

So this is where I find myself now.

I haven't anything definitive that can say whether this copy of Grose/Egan really belonged to, and was amended by, Georgette Heyer herself. The two biggest arguments for this are in the serif-lettering for headings, and the content itself. But there's no question that what I do have is an annotated variation of Grose/Egan that has not been published and likely was never meant to be. It's unquestionably a resource in its own right. That alone makes it intriguing. I'm not the least interested in selling it. Regardless of who did it, it has become one of my small treasures.

But if it's Heyer's, why wasn't it with her other books? The answer, literally, is who knows? Every time I've ever moved, books have gone missing. But I've reached an age at which I've coped with a lot of death, and a lot of estates, both large and small. Sometimes the reason for losses is obvious. My brother Bobby ran a Green magazine, and lived far out in the country in Texas. When he died, his house was broken into and trashed before I could get there, and many family belongings are gone. But this isn't usually a question of thievery, or even of borrowing. When people die, stuff goes missing. It's just part of the messy business of death.

So, this is my SOS, my call for help. Does anyone out there see something familiar in the pictures? Can anyone contribute more to solving this ongoing mystery?

CONTACT ME AT: avonkannon@aol.com

• • •

WORKS REFERENCED

Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, 1611.

Queen Anne’s New World of Words, A Dictionarie of the Italian and English Tongues, 1611, by John Florio. Also, alongside the term “Button,” to which the note has added the vulgarism “making buttons,” a later revision of Florio is cited, from 1659, The Dictionary of Italian and English, by Torriano.

A New Diurnal of Passages Printed and Published by Henry Elsing – this was an old newsbook, precursor to the newspaper, in the Grub Street days. Often a “quarto,” meaning eight pages long. This one is dated June, 1643.

The Pursuits of Literature, 13th edition, 1805, no author listed. This was a long and very popular satirical poem mocking intellectuals of the day, composed at the end of the 19th century by Thomas James Matthias, who was also a scholar of Italian.

The True Anti-Pamela, Memoirs of Mr. James Parry – not to be confused with the more famous Anti-Pamela by Grub Street scribbler Eliza Heywood – One of several satires of the nauseating 1740 novel Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded by Samuel Richardson.

Mercurius Infernus, or News From the Other World, this being another Grub Street product, a bawdy periodical from the 1650s, one of several with similar titles. It is cited as the source within another source, James Peller Malcolm’s Miscellaneous Anecdotes Illustrative of the Manners and History of Europe During the Reigns of Charles II, James II, William III and Queen Anne.

Mercurius Pragmaticus, a tragi-comic play enacted at Paris, 1641. The play is also listed as Mercurius Britannius.

David Erskine Baker, Biographia Dramatica, or a Companion to the Playhouse, by David Erskine Baker, anecdotes of theatre history for the 18th century.

No author or editor is listed for a collection out of 1662 entitled, Rump: or an Exact Collection of the Choysest Poems and Songs relating to the late times – by the most eminent Wits, from anno 1639 to anno 1661.

English Proverbs With Moral Reflections, by Oswald Dykes, 1709.

“The Post of the Sign,” a poem in Volume II of Musarum Deliciae, (subtitled The Muses Recreation, Wit Restor’d) 1640. This collection bears the subtitle of Facetiae, this being a collection of limericks and jokes, poems and songs, heavy on the naughty. Lots of toilet humor.

The History of Pompey the Little, 1751, by the Rev. Francis Coventry.

Life and Memoirs of Mr. Ephraim Tristram Bates, 1756 – this forgotten novel is sometimes referred to simply as “Corporal Bates,” and some interesting articles, particularly by Helen Sard Hughes, draw the line between this work and a far more famous one that followed, Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, which was clearly, at the very least, inspired by Corporal Bates. Even names and various scenes are the same.

“Two Parsons; or the Tale of a Shirt,” in Poetical Vagaries by George Coleman the Younger, 1812.

New Dictionary of the Canting Crew – this work, with only the anonymous “B.E.” as its compiler, was published in 1698, and remained the standard dictionary of thieves’ cant and vulgarisms until Grose was published in 1785.

The Courtezan, by the author of the Meretriciad, Captain Edward Thompson, 1765. Thompson was a naval officer who also wrote plays and satires, as well as a few works about the British navy. This particular poem reads like something a bit older, and it’s fairly ribald. Most versions spell courtesan with an “s.”

“The Life of Cesar Borgia,” Chpt 7, Book Five of The Holy State, by Thomas Fuller, 1642 – the book is sometimes called by its full title, The Holy State and the Profane State. Fuller was a churchman as well as an historian, and this five-volume work is a series of essays containing archetypes illustrating good and evil.

“The Kingdom in the Rein of Charles II,” Biographical History of England by J. Granger, 1824.

“A Ballad of a Priest That Lost His Nose,” in A Collection of Seventy-Nine Black Letter Ballads and Broadsides Printed Between 1559 and 1597, Joseph Lilly, 1870.

The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, collected by James Prior, 1837.

The Great Historical, Geographical, Genealogical and Poetical Dictionary, Jeremy Collier, 1701.

Sonnets of the 18th Century and Other Small Poems, 1809, a volume put together for publisher George Kearsley of Fleet Street.

The Universal Songster, or Museum of Mirth - this is the single addition with no date, but it was an incredible collection of popular songs for every subject, published in two volumes, 1826.

“Strip-Me-Naked, or Royal Gin Forever,” a poem in The London Magazine, volume XX for 1751.

“Bardolph and Trulla,” poem appearing in The London Chronicle newspaper, Dec. 1–3 issue, 1757. This was an evening quarto that lasted until 1765.

©2020-24 Alice VonKannon. All rights reserved. Do not reprint without permission.

Maybe she's having a good laugh at my expense.

Alice Von Kannon, Author

avonkannon@aol.com

Indianapolis, Indiana

I know this is annoying, but...

This website uses cookies. By continuing to use this site, you accept our use of cookies.

Sign Up For My Newsletter

Sign up for my occasional newsletter, free book offers, new book releases, cover reveals, speaking engagements, and more. I promise, no spam, ever. And I will never share your email with anyone else. I swear on my stack of Georgette Heyer novels!

By clicking SUBSCRIBE, you'll be whisked over to the BookFunnel site which will ask for your email address and then let you download a FREE copy of The Honor of His Name as my thanks.